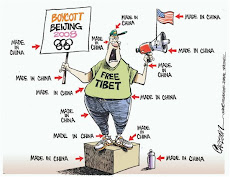

After decades of heavily financed Chinese efforts to strengthen its control over Tibet and to tame the country’s far west through gigantic infrastructure projects and resettlement of Han Chinese from the east, the outbreak of protests and riots and a fierce crackdown by Chinese security forces in and around Tibet have laid bare a harsh reality of policy failure. In Tibet and in neighboring provinces, like Qinghai, Gansu and Sichuan, where Tibetans and other ethnic minorities live in large numbers, Tibetans and Han live in closer proximity than ever before, but they occupy separate worlds. Relations between the two groups are typically marked by stark disdain or distrust, by stereotyping and prejudice and, among Tibetans, by deep feelings of subjugation, repression and fear. To be sure, there is no legalized ethnic discrimination, but privilege and power are overwhelmingly the preserve of the Han, while Tibetans live largely confined to segregated urban ghettos and poor villages in their own ancestral lands.

Chinese news programs on the events in Lhasa have reinforced an impression of separate universes that scarcely intersect — one Han and one Tibetan. The programs were clearly intended as propaganda to place the blame for riots on Tibetans and rally Han Chinese in support of a government-led suppression. Over and over, television broadcasts have repeated the same footage of rampaging Tibetans smashing shop windows and of injured, hospitalized Han, while making no mention of the widely reported deaths among Tibetans during the police crackdown that followed, nor of the underlying grievances that sparked them. Since the last widespread unrest in Tibet two decades ago, Beijing has sought to undermine separatists in what it calls the Tibetan Autonomous Region. It has invested billions of dollars, encouraged an influx of Han Chinese, and inserted itself deeply into the mechanics of Tibetan Buddhism to eliminate the influence of the Dalai Lama, who fled China for India in 1959 after a failed uprising. But real assimilation, if it were ever the goal, remains elusive. In the Tibetan capital, Lhasa, Han shopkeepers, hostel owners and others who are picking up the pieces of their lives after riots that destroyed many Chinese-owned business there spoke with scarcely concealed condescension, and often with outright hostility, of Tibetans whom they described as lazy and ungrateful for the economic development they have brought.

“Our government has wasted our money in helping those white-eyed wolves,” said Wang Zhongyong, a Han manager of handicraft shops, said in an interview in Lhasa. Mr. Wang’s shops sell Tibetan-themed trinkets to tourists, one of which was smashed and burned in the riots. “Just think of how much we’ve invested in relief funds for monks and for unemployed Tibetans,” he said. “Is this what we deserve?”. Among Han in Lhasa, comments like these stood out for their mildness. “The relationship between Han and Tibetan is irreconcilable,” said Yuan Qinghai, a Lhasa taxi driver, in an interview. “We don’t have a good impression of them, as they are lazy and they hate us, for, as they say, taking away what belongs to them. In their mind showering once or twice in their life is sacred, but to Han it is filthy and unacceptable. “We believe in working hard and making money to support one’s family, but they might think we’re greedy and have no faith.” Even among long-term residents in Lhasa, Han Chinese said they had no Tibetan friends and confessed that they tended to avoid interaction with Tibetans as much as possible. “There’s been this hatred for a long time,” said Tang Xuejun, a Han resident of Lhasa for the last 10 years. “Sometimes you would even wonder how we had avoided open confrontation for so many years. This is a hatred that cannot be solved by arresting a few people.” Tibetans, meanwhile, complain that they have been relegated to second-class citizenship, that their culture is being destroyed through forced assimilation, that their religious freedoms have been trampled upon.

A Tibetan university student in her early 20s who declined to give her name explained relations this way. “I really don’t want to talk about politics, saying whether or not Tibet is part of China. The reality is that we are controlled by Chinese, by the Han people. We don’t have any say, so in my family we don’t even talk about it.” Although the young woman said that her family was relatively well off and that she was receiving a good education, the future was bleak here even for someone like her because the system favors the Han. “I’m not even sure I can get a job after graduation,” she said. “For rich Tibetans and for officials, they send their children out to Chengdu or Beijing.” A sense of the fear many Tibetans live with could be heard in the comments of a religious leader in Aba Prefecture in Sichuan Province, the site of a protest by monks and others earlier this week in sympathy with the Lhasa demonstrations, and the scene of a subsequent fierce crackdown. “I only know that the Communist Party is good, that they are good to us,” said the religious leader, Ewangdanzhen, when asked about official explanations that have blamed the Dalai Lama for the protests. “I only believe in the Communist Party. Splitting is bad. We want unity and harmony. We don’t have any contacts with him and we don’t need to contact him.”

Far from giving up on their way of life, though, or renouncing their attachment to the Dalai Lama, the exiled spiritual leader the Chinese government has long vilified as a separatist, or “splittist,” most Tibetans interviewed while dodging heavy police checks during a 450-mile road trip through Tibetan areas in Gansu and Qinghai provinces professed near-universal devotion to the Dalai Lama, and vowed to continue resisting government attempts to control their faith. “All Tibetans are the same: 100 percent of us adore the Dalai Lama,” said Suonanrenqing, a 40-year-old resident of a Tibetan village in Jianzha County in Qinghai Province. Asked about China’s decision to commandeer an ancient Tibetan religious rite and select the Panchen Lama, the second-highest figure in Tibetan Buddhism, in 1995, and the implications for how Beijing would manage things after the Dalai Lama, who is 72, dies, Suonanrenqing’s response suggested indefinite tensions between Chinese and Tibetans. “We’re not sure if it’s true that the Panchen was appointed by the government, but if it is true, we cannot support him,” he said. “We wouldn’t support a Dalai Lama appointed by the government either. These people should be chosen by monasteries.”

Although Suonanrenqing spoke candidly, worrying only at the end of a lengthy conversation if his comments could bring him trouble, many conversations with Tibetans began with nervous denials that they knew anything at all of the events of Lhasa. Their wariness was warranted by a severe security crackdown in clear evidence wherever Tibetans live in large numbers. After dodging one police roadblock, a reporter making his way late at night toward a town in Gansu Province where Tibetans had protested in sympathy with the Lhasa demonstrators the day before was set upon by plainclothes police officers at a highway tollbooth and forced into a nearby building for questioning before being turned away. The following day, when visiting Taersi, an important Tibetan monastery in Qinghai Province, the reporter was closely tailed by plainclothes police officers who were seen videotaping his conversations with local monks. “I have no idea what’s happening in Lhasa,” said one 32-year-old monk, who agreed to sit and chat in a small restaurant with a foreign visitor but apparently felt the topic was too dangerous to touch upon. “We don’t have anything to do with that.”

Despite the vigilant police, the nearby Lijiaxia Valley, a starkly beautiful area dominated by the Yellow River with craggy, desiccated mountains and windswept farmland, Tibetan villages were easy to spot by the colorful prayer flags that flew from roofs and hilltops. Here, many initially claimed to know nothing of the events in Lhasa. But some quickly dropped this cautious pose. One poor villager, who rolled homemade cigarettes using old newspaper, was aware that Chinese news broadcasts were showing footage of Tibetans rioting in Lhasa. “Have there been any pictures of Tibetans getting killed?” he asked. When told no, he nodded his head and said, “Of course not.”

By Howard W. Lynch

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Disclaimer

No responsibility or liability shall attach itself to either myself or to the blogspot ‘Mozlink’ for any or all of the articles/images placed here. The placing of an article does not necessarily imply that I agree or accept the contents of the article as being necessarily factual in theology, dogma or otherwise.

Mozlink

No comments:

Post a Comment