January 14th. Financial Times - For a brief moment, Kenyans seemed to have summoned the collective muscle necessary to hold their rulers to account. Across the country on December 27, they assembled peacefully and in record numbers to vote. As results came in from a parliamentary contest that ran alongside presidential polls, it transpired that a generation schooled in the post-colonial politics of patronage and graft was being shown the door. There were the makings of a watershed for Africa. Alongside the eviction from parliament of nearly half the cabinet, an incumbent leader, Mwai Kibaki, looked set to be ousted and a second consecutive constitutional transfer of power – unprecedented on the continent – seemed imminent. If there were grounds to doubt that a new government would fare better at meeting demands for social justice, these were tempered by a surge of confidence among Kenyans that if incoming ministers failed, they too could be removed peacefully.

January 14th. Financial Times - For a brief moment, Kenyans seemed to have summoned the collective muscle necessary to hold their rulers to account. Across the country on December 27, they assembled peacefully and in record numbers to vote. As results came in from a parliamentary contest that ran alongside presidential polls, it transpired that a generation schooled in the post-colonial politics of patronage and graft was being shown the door. There were the makings of a watershed for Africa. Alongside the eviction from parliament of nearly half the cabinet, an incumbent leader, Mwai Kibaki, looked set to be ousted and a second consecutive constitutional transfer of power – unprecedented on the continent – seemed imminent. If there were grounds to doubt that a new government would fare better at meeting demands for social justice, these were tempered by a surge of confidence among Kenyans that if incoming ministers failed, they too could be removed peacefully.

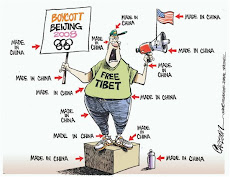

But it was not to be. In the event, questions about the veracity of a quarter of a million or so ballots that delivered Mr Kibaki an unexpected second term as president got in the way. Kenya has since been pitched into its most serious crisis since independence from Britain in 1963, disrupting a narrative that sees Africa overcoming tyranny and conflict and moving steadily towards more accountable forms of rule. “I fear the Afro-pessimists are going to have a field day,” says Andrew Rugasira, an entrepreneur from neighbouring Uganda, recognising that Kenya’s fall will reverberate far beyond its borders. On cue, there have been rumblings about whether a continent still riven by ethnic discord and beset with development challenges is ready for democracy after all – or, at least, whether the cost in blood is worth paying. China has been quick off the mark, with the People’s Daily, mouthpiece for the ruling Communist party, suggesting on Monday that “western-style democracy simply isn’t suited to African conditions, but rather carries with it the root of disaster”. In theory, the dynamic of elections in Africa should be changing. Economic growth averaging nearly 6 per cent in recent years has started to produce a better-educated and vocal middle class in many countries, while rapid urbanisation has begun to erode traditional ties to tribe and clan among a huge underclass.

Yet Kenya’s election has exposed the country’s ethnic divisions, confirming that Africans still tend to vote for who they are rather than what they believe in. Meanwhile, the manipulation of the vote count has borne out another familiar trait: that, regardless of the consequences, African leaders rarely miss an opportunity to cling to power. “Democracy is not working in Africa,” says Nasir el-Rufai, a former Nigerian government minister who helped spearhead economic reform under former president Olusegun Obasanjo. “It is either those with money who determine the result or those in power who decide who wins.” In Nigeria’s elections last year, it was a combination of both. A day that should have been celebrated as the first transfer from one elected civilian administration to another in a history littered with military coups was marred by every kind of electoral fraud in the book. Even in South Africa, still a model for much of the continent, there are concerns about the enduring dominance of the African National Congress. With the Democratic Republic of Congo teetering on the edge of renewed conflict only 18 months after the United Nations ploughed $500m into the country’s elections, it is possible to argue that most of the main poles of economic development in Africa are, as Mr el-Rufai puts it, “democratic basket-cases”.

The consequences for Nigeria – home to one in five Africans – may yet be severe. But there was no immediate eruption as a result of last year’s rigging. This appears to have contributed to complacency in international circles over Kenya, where politicians had mobilised along ethnic lines, the race was much tighter and popular expectations were considerably higher. “One of the issues which is raised by Kenya is whether these countries can afford to have a true electoral system at this point or whether the risks are too great,” says Marina Ottoway, an expert on democratic transitions in Africa and the Middle East at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. “I am not saying we should never push for elections,” she continues, “but the outcome can be a real setback and it is disturbing that a lot of western organisations, both governmental and non-governmental, assume that it is always the right thing to do.” Weighed against this line is Africa’s history of murderous despots. Moreover, those countries that have been convulsed by violence as a result of faulty polls have often been those whose institutions have been most weakened beforehand by the ravages of personalised rule.

Twenty years ago only a handful of sub-Saharan Africa’s 48 countries could be considered democratic. But as the cold war was ending, pro-democracy movements and opposition groups were pushing the boundaries of political freedom in the one-party states predominant across the continent. At the same time, Britain, France and America were loosening ties with client dictatorships and encouraging multilateral lenders to make multi-party politics a condition of continued aid. Evoking Harold Macmillan’s famous speech 30 years earlier, when independence dawned for Britain’s African colonies, François Mitterrand, the late French president, recognised in 1990 that a “wind of change” was blowing. The political transitions that resulted have ranged from the miraculous, in South Africa in 1994, to the apocalyptic. Nearly 10 per cent of the combined populations of the tiny former kingdoms of Rwanda and Burundi have been killed in the struggle for political supremacy between the Tutsi and Hutu ethnic groups, underlining the danger across the continent of politics that draw on identity rather than ideology. But these extreme events can now be seen in the context of hundreds of elections that have taken place. In many cases, voting has simply added trappings to a modernised form of one-party rule, where incumbent regimes use patronage, the control of electoral machinery and oppression to maintain a perpetual grip on power – until war breaks out. Inflows of foreign aid, meanwhile, have inadvertently compounded a lack of accountability. Donors mostly promote democracy, but when they contribute as much as 60 per cent of national budgets, they tend to want to call the shots. Nor have greater political freedoms translated into economic development and greater social justice. Where there has been a resurgence of economic growth, as in Kenya, this has often sharpened inequalities, raising the stakes at election time as well as the potential for violence. “High economic growth can actually be politically destructive. It eats away at the social fabric when it is perceived that only one group is benefiting,” says John Githongo, Kenya’s former anti-corruption chief, who exiled himself in the UK three years ago.

Yet in a handful of the most promising cases in Africa, elections have not only delivered political change and improving leadership, they have also become routine. Electoral commissions have evolved as independent institutions capable, if not of enforcing results, at least of resisting manipulation, while political parties have begun to trade across ethnic boundaries. Technology has also helped. The proliferation of mobile phones has combined with aggressive reporting in the media, notably on independent radio stations, and the advent of the internet to make it more difficult to rig, while increasing scrutiny of what officials do once they are elected. Ghana is one example. “I think politicians [in Ghana] are constantly aware of the next election even a week after they have won. Whatever they do in government they know that the day when they will have to account for their actions will come,” says Elizabeth Ohene, an education minister in Ghana’s cabinet. Alongside Ghana, Benin, Senegal, Zambia and more recently, Sierra Leone, Kenya was until recently among a select group on the African mainland to have experienced the peaceful transfer of power from one political leadership to another. “The actual polling by the public seems to have gone pretty well,” says Gladwell Otieno, head of the Nairobi chapter of Transparency International, the anti-corruption watchdog. “There were some logistical problems that are to be expected. But people greatly wanted a change and were willing to queue for hours and hours to get it,” she continued.

When national results at the electoral commission differed widely from local counts, Kenya became an important test case for international diplomacy. Britain, the EU and US have all said they will not be going back to business as usual and are working on a set of measures aimed at forcing negotiations. Yet the record of donor governments in recent years suggests that realpolitik usually triumphs, especially when the country is economically important or of strategic importance in the US war on terror. Kenya is both. “Although they [donor governments] criticised the conduct of the Ethiopian elections in May 2005, those in Uganda in February 2006 and in Nigeria in April 2007, they have taken little concrete measures to show their disapproval in the end, all opting to work with the elected government rather than to isolate it,” a Citibank analysis of the Kenya polls concludes. Ms Ottoway argues that of the recent electoral transitions, the ones that stand out as successful involved carefully negotiated processes that took into account the fears of both minority and majority groups. South Africa is the prime example. Nigeria, for all its democratic failings, is another. In hindsight, the constitution left to elected civilians by the military in 1999, looks purpose-built to prevent the kind of ethnic strife that Kenya is experiencing. Political parties are obliged to build support across religious and ethnic lines, and there is an unwritten rule that the presidency circulates between the country’s three most powerful regions. Many African countries, however, have yet to tailor political systems inherited from former colonial powers to the needs of their own societies. It is no coincidence that the same group in Kenya that has, arguably, hijacked this year’s elections, also stymied efforts in 2004 at a national conference to create a new constitution devolving more authority to regions and limiting the powers of the presidency. While Kenya has had several elections, it therefore has yet to experience a transition to more equitable rule. Instead, the same elite has ended up sharing the spoils of office, even if sometimes it has worn different political colours. “Kenya’s ultimate tragedy would be that if, at the end of this terrible ordeal, nothing really changed,” says Michael Power, an Africa analyst at Investec, the investment bank.

By William Wallis

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Disclaimer

No responsibility or liability shall attach itself to either myself or to the blogspot ‘Mozlink’ for any or all of the articles/images placed here. The placing of an article does not necessarily imply that I agree or accept the contents of the article as being necessarily factual in theology, dogma or otherwise. Mozlink

No comments:

Post a Comment